Society for East Asian Anthropology

Mengzhu An, Jing Wang & Wei Ye

January 9, 2024

During #A4Revolution, protestors used blank white paper to express their voices while remaining in the shadows of state censorship and surveillance.

On November 26, 2022, a college student in black clothes, black hat, and black mask was standing on campus, holding aloft a blank piece of white paper. A middle-aged man walked up to them and ripped away the paper from their hands.

“Why did you take away their white paper?”

“What threat does the white paper pose?”

The questions of angry observers remained unanswered. Even after the paper was taken away, the young Chinese protestor stayed in their posture, holding nothing in their hands.

This scene at Nanjing Media College, in Nanjing, China, was captured in a video clip that went viral online. The determined image of a young Chinese person holding a blank white paper was so powerful that it became an icon in what was the then-emerging #A4Revolution protests. In small and large cities across China, people stood in the cold night air holding up sheets of white paper, silently demanding freedom from the extreme levels of surveillance and control enacted under the country’s zero-COVID policies. The protests against such policies that broke out around the world have come to be considered as the most influential public defiance in China since the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. What can a blank piece of paper do? As this article shows, blank white paper presents both strategic opportunities and ambiguities for social movements in China. In the case of #A4Revolution, protestors used blank white paper to express their voices while remaining in the shadows of state censorship and surveillance.

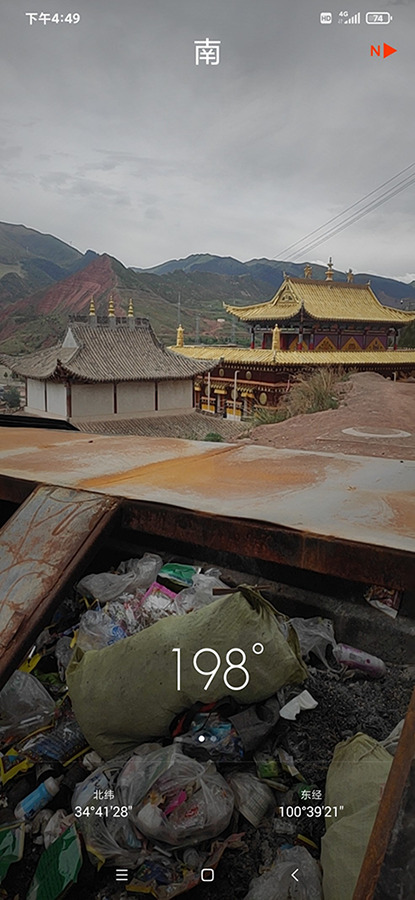

IMAGE CREDIT: NONENULLNAN

IMAGE CAPTION: The Elephant

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A grayscale image showing a person with a baseball cap, holding an A4 paper, facing a large elephant across a diagonal divide of light and shadow. Hashtags #白纸革命 and #A4Revolution are written below.

Why White Paper

White paper originated from local protests that were triggered by a tragic fire at a Uyghur-majority residential building in Ürümqi on November 24, 2022, killing at least 10 people living there. Some blamed the incident on the government’s zero-COVID restrictions, where the discovery of one COVID case could lead to the grounding of all residents until the neighborhood became free of COVID again. Such long-term lockdowns severely limited residents’ capacity to respond to emergencies, such as the fire in Ürümqi. But people stressed that this disaster could have happened anywhere, not just in Ürümqi. One Weibo user posted, “After waiting for more than a hundred days, what we got was not freedom, but a raging fire and thick smoke.” In another viral post, Ürümqi officials’ irresponsible explanation of the fire was sarcastically rephrased as “The road is open, they don’t run,” implying that residents were at fault for not being able to escape the disaster. Such criticism against government officials was met with swift censorship. The accumulated resentment and anger were partly why people began to appear on the streets across China with blank paper on the evening of November 25, 2022.

In contemporary China, people have long strategized means of expression to deal with government censorship and surveillance. Netizens learn to maintain anonymity and adapt to the ever-changing codewords and techniques to discuss “sensitive” topics online. Such tactics of playing hide-and-seek with Big Brother were also evident in the protests against zero-COVID policies. The #A4Revolution was particularly “ghostly,” in Jacques Derrida’s terms, as it engaged in invoking the “visibility of the invisible” and “tangible intangibility.” Protests painted slogans in unmonitored public restrooms, posted flyers on telecom poles in the dead of night, communicated through anonymized channels, and stayed masked at events to avoid identification.

But this did not mean that they were immune to surveillance. The omnipresence of state censorship and violence is equally spectral. As Derrida says, “We do not see who looks at us.” In the video clip referenced at the beginning of this article, the white paper was eventually taken away without explanation from a silent protestor by a street-level bureaucrat who also remained silent. Political dissent is met by arbitrary crackdown through vague charges such as “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” (xunxing zishi) or a “pocket crime” (koudai zui). Though existing before the pandemic, such control and violence have been greatly intensified and normalized under zero-COVID policies. Always in danger, white paper protestors consciously used anonymity and silence as a counter-strategy. Not a single word was written on the countless sheets of white paper, but their silence loudly defied state tools of repression.

Protesting with provocative silence, like holding a white paper, is not unique to China. Following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian streets were swept by antiwar protests. In March 2022, the Russian Federation parliament passed a law that criminalizes the spread of “fake information” about the Russian army and forbids referring to the invasion as war. The protestors with “no to war” signs became targets for arrests based on this law. As with the #A4Revolution, Russians came up with creative ways to express dissent against their authoritarian government. One woman, for example, held a paper saying dva slova (two words), gesturing to the forbidden slogan net voine (no to war), and other demonstrators just held blank paper, like their Chinese counterparts. These show what white paper can do as a symbol of civil resistance against authoritarian regimes around the world.

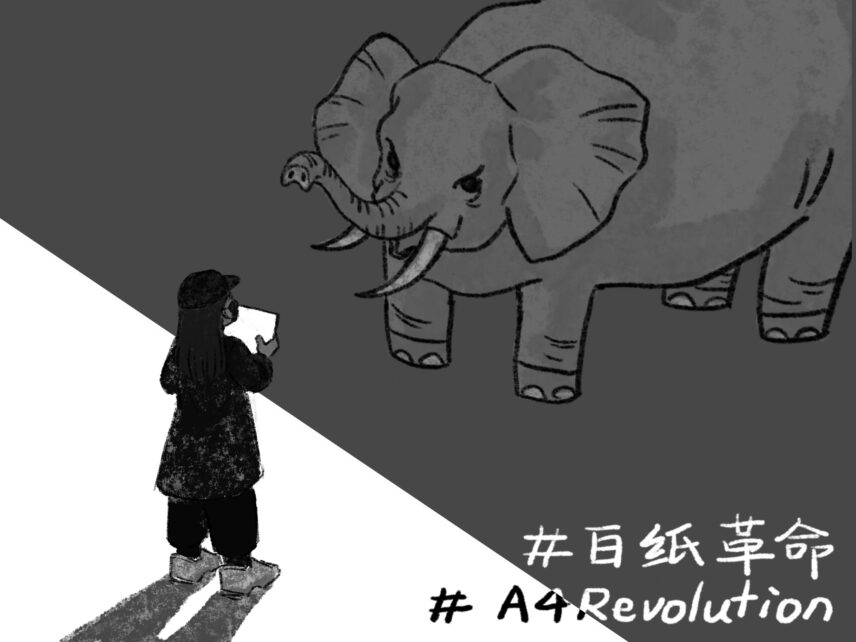

A four-panel comic. The first panel draws a huge red two-dimensional code on the floor, which is erased by a person in the second panel. The third panel leaves only the person standing on the floor. In the fourth panel, many people walk around with red traces of the code on them, symbolizing the lasting impact of the trauma caused by the zero-COVID policies that cannot be erased. This four-panel comic illustrates how even though the government may have tried to erase the visible signs of violence, the psychological scars on those who experienced it cannot be easily healed.

IMAGE CREDIT: NONENULLNAN

IMAGE CAPTION: luminol

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A four-panel comic. The first panel draws a huge red two-dimensional code on the floor, which is erased by a person in the second panel. The third panel leaves only the person standing on the floor. In the fourth panel, many people walk around with red traces of the code on them, symbolizing the lasting impact of the trauma caused by the zero-COVID policies that cannot be erased. This four-panel comic illustrates how even though the government may have tried to erase the visible signs of violence, the psychological scars on those who experienced it cannot be easily healed.

From Ghostly Public to Fragmented Solidarity

Both in China and overseas, protestors shared a common challenge of not knowing what to chant. Without a singular rallying cry, blank white paper could be used to obscure dissonant claims or internal rivalries within the movement. While some simply held up blank sheets of paper in silence, others cursed Xi Jinping and called for his removal. Fearing that such explicit words would give the police an excuse to enact suppression, many insisted on a more practical demand to end the zero-COVID policies and return to a normal life. Meanwhile, the national anthem sounded at some of the rallies, which was intended to strengthen solidarity, but also provoked mixed reactions. Some non-mainlanders who originally came to show support left the rally as soon as they heard it out of distaste for such nationalistic symbols. Beyond holding up blank paper, it was a challenge for protesters from different groups to identify any other code or symbol upon which to build connections.

The disputes over symbols, slogans, and language on-site and after the protests reflected the varied agendas within the #A4Revolution. This revolution became a reincarnation of public grievances and a gathering of revenants, including the suppressed protestors of Hong Kong’s anti-extradition movement, the Uyghurs and Tibetan victims of anti-religious policies, and feminists and young dissidents in exile. The mishmash of revenants infused the superficial solidarity with implicit fragility, which reflects the precarious conditions of civil disobedience and the limits of public protest under authoritarian rule.

Although the vast majority of the dead and injured in the fire that triggered the #A4 Revolution were Uyghurs, some of whose families had been imprisoned in the government-run “re-education camps” or exiled overseas, the protests everywhere were dominated by Chinese-chanted slogans centered on the demands of urban Han people. One anonymous Han Chinese woman criticized this for overlooking the structural violence imposed on the Uyghur community by the Chinese state. At the vigils in two cities in the United States that some of us attended, young women spoke out against the misogynistic words that some male participants used to curse Xi Jinping and the CCP. They preferred chanting slogans such as “End Patriarchy” and “End Police Violence.” However, when such gendered frictions and disparities were pointed out in online group chats after the rally, they were dismissed by some people as “overly sensitive.” Ironically, while many women’s complaints were met with contempt, they made up the majority of those arrested and unexpectedly became the iconic symbol of this revolution.

After the Revolution

In December 2022, shortly after the rise of the #A4Revolution, the Chinese government rolled back its stringent zero-COVID policies. But it is debatable whether this was a gesture of surrender to the white paper protesters. In the aftermath of the #A4Revolution, the police continued to arrest those who were presumed to have participated in the #A4Revolution. Several female participants in vigils in Beijing were detained for about four months. The ghostly publics of the A4 movements and their temporary solidarity seemed to have dissipated, or so we thought—until a female protester suggested otherwise. With difficulty, she delivered a message from the detention center:

“Even though they made us feel like we were betraying each other during the interrogation, I still believe that we are in solidarity. On New Year’s Eve, A, B and I [all arrested protestors] had a concert through the doors of the prison, singing songs together . . . and we will join you again, start preparing.”

This message has circulated anonymously on encrypted social media platforms. It has inspired a renewed belief in the significance of resistance and the potential for solidarity. “A specter is always a revenant,” and the ghostly publics of the A4 movements will continue to haunt the future.

Some participants of the White Paper Movements made cards in solidarity with the girls in detention, with their faces drawn and names written, as well as the words “Release Our Friends.”

CREDIT: @ANOSARTOR

IMAGE CAPTION: Girls in detention.

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: Some participants of the White Paper Movements made cards in solidarity with the girls in detention, with their faces drawn and names written, as well as the words “Release Our Friends.”

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Anastasiya Miazhevich for sharing her observation of the anti-war protests in Russia as a comparative perspective. We also want to thank the two editors Jieun Cho and Aaron Su for their generous feedback and editorial work.

Jieun Cho and Aaron Su are contributing editors for the SEAA section in Anthropology News. This piece is part of the SEAA series “The Future of the ‘Public’ in East Asia.” Contact them at jieun.cho@duke.edu and aaronsu@princeton.edu.