Olivia YA Dung

On an August evening in the 1990s, Chengyen—a Buddhist nun who founded the Buddhist lay organization Tzuchi in 1966—was disturbed by the overwhelming amount of garbage in a night market on her way to give a speech. During this period, after the lift of martial law in Taiwan, Tzuchi was expanding rapidly and had become the largest and most prominent Taiwanese NGO with more than ten million members and ninety thousand certified commissioners worldwide. Also at this time, Taiwan was facing a lack of landfill space and incineration capacity for waste disposal.

Later on that evening, in response to the audience’s enthusiastic applause for her speech, Chengyen called for a movement to obliterate garbage. The speech, later referred to as “using applauding hands to recycle,” is remembered today as the legendary beginning of Tzuchi’s involvement with recycling. That night, a twenty-four-year-old woman from the audience took Chengyen’s words to heart and initiated waste paper collecting in her neighbourhood. The news quickly spread among Tzuchi’s practitioners—the certified commissioners. Gradually, the size and scale of the Tzuchi recycling community grew as the organization carried out Chengyen’s wish, and as her followers worked towards “reserving pure land in the human world,” to promote green consciousness and recycling.

Twenty-six years later, today Tzuchi’s national recycling programme is comprised of 86,594 volunteers, 8,626 community recycling bases, 900 trucks, 316 large environmental education stations, and a network of cadres and administrators across the nation. Miscellaneous recyclables—ranging from plastic bags to household appliances—are systematically collected from markets, shops, residential communities, and businesses by the members. In the recycling stations, volunteers and commissioners squat on low stools, spending mornings and afternoons dismantling and classifying valuable discards: separating copper out of motors, removing small screws from old VCR tapes, cutting out blank white paper from the parts tainted with ink.

“The more meticulously you separate, the better price you get,” one Tzuchi recycling cadre responded to my stunning facial expression when I first saw Tzuchi’s intricate system of classifying plastic packaging materials into eleven categories. “We don’t do this [recycling] for profit, but rather for the earth. It’s like what the Dharma said, if the earth is not at peace, there will be no peace in human minds.”

Plastic bag classification: the referencing sample board can be found in numerous recycling stations across the country (© Olivia Dung 2016)

“Why come to Tzuchi recycling?” I asked Ying, a 68-year-old female volunteer with whom I spent three months separating plastic bags together. It was 11:20 am. Ying and I had just finished sorting four bags of cloth packaging, and drying three bags of disposable raincoats. Ying is a former construction worker. One day after her retirement, she walked into one Tzuchi abode and asked about volunteering. “I couldn’t just sit at home and stare at the television. It drives me crazy. Here is good. You work, you talk, and then the day passes by.” “But don’t you sometimes find this work dirty or boring?” I continued to ask. “Not at all. The more I do, the happier I get,” Ying replied without lifting her eyes from wrapping up the bags. “Why?” “[silence] it’s…it’s… it’s doing huanbao. To make the earth cleaner, isn’t it better? Yeah. And once you’re busy, you become devoted.”

In Tzuchi, “doing huanbao” (做環保) is almost synonymous with “recycling.” The meaning of “huanbao”, an abbreviated term for “environmental protection”, is however multilayered and contextualized religiously in Tzuchi recycling. The organization applies certain tenets of Buddhist thought in their understanding of global environmentalism, addressing the “underlying” spirituality in everyday practices of recycling.

“Like the cycle of four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter—there is a cycle of all matter and beings; these are the eons of formation, existence, decay and dissolution (成住壞空). […] Recycling is to reuse and resurrect disposed materials, to let spirits of materials come back to life for their own purposes. It is a material reincarnation.”

This quote from Chengyen in her book Purification From the Start (2010) illustrates a Buddhist imaginary of recycling as transforming artificial matter into natural beings by inserting a “natural” law in the process—reincarnation. In so doing, the mundane physical tasks of material collection are made into a series of religious practices. And, dealing with endless waste materials has become a sort of religious awakening. In the process of working hard and engaging with waste, one’s mind is liberated from secular materialism and utilitarianism. It molds mind and disposition into a state which dismisses attachments to worldliness.

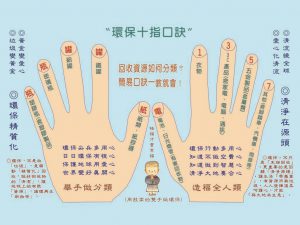

Tzuchi handout flyer: “ten mnemonic chants for environmental protection” (慈濟環保十口訣) (source: Tzuchi handout flyer)

This way of perceiving recycling resonates with how Tzuchi understands the relation between mankind and nature. For Tzuchi, environmental issues, from global warming to waste problems, are the “symptoms” of a physical reality of Sida Budiao (四大不調)—The Disharmony of the Great Four. Sida Budiao, however, is not a literal description of the four elements: earth, water, fire, and wind. Rather, it depicts an abstract, abnormal, and “unhealthy” status of an organic being—be it humans, the earth, or the universe as a whole — when the regularity is disrupted.

Instead of seeing the causes of the disharmony of the earth (or, “environmental crisis” in other words) merely as a structural malfunction of today’s economic and political system, Tzuchi employs another Buddhist concept of the Kleshas (人心五毒), the Five Afflictions of the Human Mind, as the driving force towards the disharmony of our planet: because we are lazy; we drive instead of walk; we are greedy; and we consume and produce more than we need.

In Tzuchi’s environmental discourse, the relation between humans and environment is therefore not dichotomously divided, as seen in anthropocentric styles of environmentalism which assume that humans need to protect nature from culture. The physical task of recycling, for Tzuchi, is a method to purify the polluted minds which eventually lead to a polluted world. This perspective on how humans and nature are one inseparable organic being attracts a specific group of people—mostly the elderly—to join the army of Tzuchi recycling volunteers.

On the other hand, from volunteers such as Ying’s perspective, the mindless and repetitive tasks of assessing, sorting, and dismantling provide a sort of therapeutic function, which is not altogether different from the concept of occupational therapy. The social goals of environmental protection in Tzuchi recycling are therefore deeply intertwined with individuals seeking salvation. In other words, the process of remaking waste in Tzuchi becomes a means for practitioners to remake themselves.

Olivia YA Dung is a Ph.D. candidate in Area Studies at Leiden University. Her dissertation fieldwork examines the practices and discourses of recycling among various stakeholders participating in the national recycling system in Taiwan.