東北からの声https://tohokukaranokoe.org/

David H. Slater

Note: This project was supported by grants from Toyota Foundation, a Kaken grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education, and various sources from within Sophia University. A more detailed outline of the archive can be found here: Public Anthropology of Disaster and Recovery : “Archive of Hope”(希望ア–カイブ)

Of all of the data that has inundated us during this digital revolution, from the flow of images and texts to tweets and links, we have also experienced a loss in our attention to the human voice in narrative. Perhaps this became especially acute for me in the aftermath of the March 11th, 2011 triple disasters in Japan. Because of the disruption of time and place, of life course and communities, oral narrative has emerged as a privileged way to understand and share this condition within and beyond the affected communities. Digital media has also, somewhat paradoxically, allowed voice and face, those most analogue elements of data, to be gathered and made accessible in ways that were not before possible. In “Voices from Tohoku” we have collected our own interviews into the largest archive of video oral narratives on the 3.11 disasters, and one of the largest oral narrative projects on any topic.

The archive is the work of students at Sophia University who have conducted more than 500 hours of semi-structured interviews throughout Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures from the spring of 2011 until 2015 (when we ran out of money). Thus, unlike some other projects which are primarily portal sites that link to and aggregate other data, our archive contains only the data we have generated ourselves. Our videos are people telling their own story in their own words.

Most interviews are between 1 and 2 hours long, and the full scholarly archive contains all of these unedited digital videos, almost completely transcribed and thus searchable, which we have made accessible to scholars from Japan, Asia, Europe and North America. There is also an open “community” website with thousands of shorter clips of 1-3 minutes. These clips are geographically and thematically tagged. The website has more than 80,000 hits now—which in the world of oral narrative are rock-star numbers. Our site is plain without impressive graphics and only basic coding. Because it is designed primarily as a way for us to share our interviews with our narrators in Tohoku, it is only in Japanese now (but Google Translate can give you a rough idea).

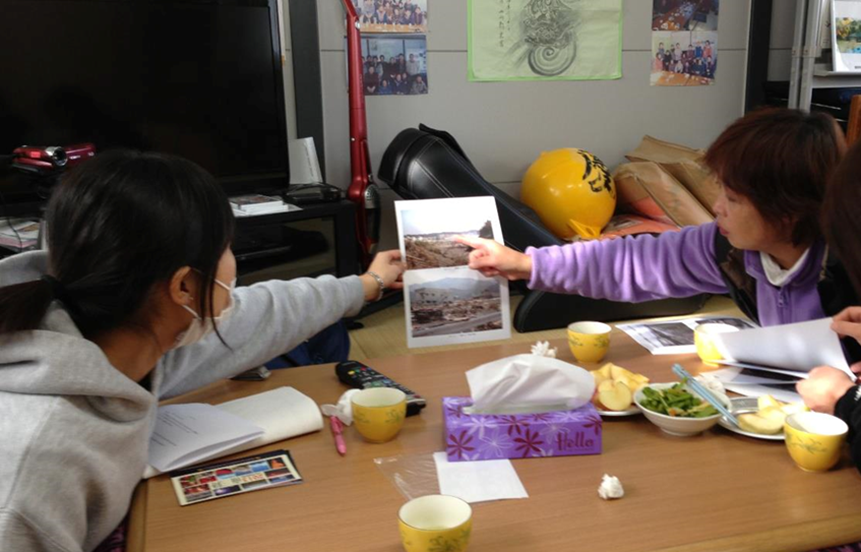

We did not start as a research project at all. In the spring of 2011, students from Sophia University trucked up to Tohoku to volunteer, working wherever we were most needed until one day, upon seeing our cameras, an old woman in a Miyagi “temporary” housing unit invited a group of our students in because “she had something to tell us.” That “something” ended up lasting many hours over 3 days. She felt that her own government was not very interested in what she, or any local, had to say, and the mass media had already plotted their pre-set narratives. She, and hundreds of others, would rather we took time to record their stories than dig tsunami mud from their living rooms. While this was surprising at the time, it was something we were trained to do—oral narrative interviewing. From then, we began a new schedule: volunteer work in the morning, interviews in the afternoon, and usually nomikai drinking parties at night. Most of my students from Tokyo, not Tohoku. As such, they were enough “outsider” so that local residents wanted to tell them their stories. And when you’ve spent hours, days and weeks in a community doing volunteer work, it is much easier to generate the sort of goodwill and understanding that is so vital to good interviewing.

The archive did not emerge until 2013, after we had been interviewing for almost two years, as we were trying to figure out what we would do with our interviews. In 2012, after an interview, we were told by one fisherman in Rikuzen Takata: “Don’t be like those other ‘researchers’ who just take our stories and disappear. We are busy people; we are only telling you this so you will DO something with them.” This website is our effort to DO something that will be meaningful to the narrators, to share their stories with each other and with a wider audience.

Our archive is characterized by not only its scope but also by its diversity. Some narrators start their story on the ‘day of,’ (あの日), as a point of references from which they then move backwards and forwards. (We never asked directly about that day until they brought it up—sometimes it is as important to find ways to forget as it is to remember.) Others start speaking as representatives of their community, offering up continually refined set pieces in ways that (we came to think) sought to reestablish some coherent and presentable face for both the individual as well as the community. There are many hopeful stories of heroic struggle in overcoming challenges, and there are just as many “crying stories” of pain and suffering—but it is almost always more complex than that. At times, the narrators are viciously critical of conceits and duplicity—of the State, of TEPCO (the electric company that runs the Fukushima reactors), or even their neighbors and themselves. Other times, our narrators were halting, feeling their way through a topic, talking to and for themselves as much as for us.

Narrators’ page for Ishinomaki. Each narrator has 3-5 shorter clips, thematically coded and transcribed. David Slater

An archive of scope, structured in a coherent fashion that enables efficient accessibility will outlive most journal articles or books. Moreover, this research model has also allowed us to more fully involve undergraduate students over an extended periods of time than I never imagined, and to collaborate with other researchers, communities, NPOs and social movements in ways that have created scholarly, political and civil potential, that we and others, are only beginning to appreciate and develop.

Sadly, we no longer have funding for Tohoku travel, but we are doing great oral narrative projects in Tokyo of anti-nuke movement, youth protests, irregular labor, homelessness and social justice issues. I am always only too happy to explain how we do what we do, and to collaborate on future projects with others.

David H. Slater is the Director of the Institute of Comparative Culture, and professor of cultural anthropology in the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Graduate Program in Japanese Studies at Sophia University, Tokyo.