Annemarelle van Schayik

On the wall are handwritten notes and posters, yellow ribbons are distributed and thousands of students from various Hong Kong universities listen to student speeches and calls for action. It is September 22, 2014, the first day of a weeklong student class boycott. The kick-off was held at the Chinese University of Hong Kong [CUHK], but the following days students could be found outside the Hong Kong Government Offices where professors were giving lectures on democracy and freedom of speech.

Five days after the start of the student class boycott a small group of student activists would successfully climb over the fences into Civic Square, as coined by the protestors. Until July 2014 the square had been open and it had acted as a demonstrating space. Protestors saw the move to close fences at night as an attack on the freedom of assembly. A freedom considered a core value in Hong Kong. Storming the square was considered illegal and occupants were forcefully removed and taken into police custody.

The fate of the arrested was unclear for many hours and the day after Hongkongers of all walks of life took to the street. Due to poor management of the constant stream of people, the public poured onto the streets. As the evening fell, in response to the swelling number of people occupying key roads in Hong Kong’s Central district, the police used pepper spray, fired tear gas and employed batons in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

The use of police force shocked the city. Western media were quick to jump onto the bandwagon and write about it as a student movement. But little was written about the students who did not participate.

The movement seen through the lens of Hong Kong students when they were not protesting on the streets gives a glimpse into their political consciousness. Most students did not camp outside the Government Offices, they were not on the streets 24/7 and therefore stories of those who were not at the forefront are left untold. I was 5 minutes away from the protests when the police fired teargas, but decided not to join the ranks. Not because I did not care, but because I do. I came to Hong Kong seven years ago for studies and since then have slowly felt a sense of belonging to the city. While my heart told me to go out and stand besides my friends, my students and my fellow city residents, I did not.

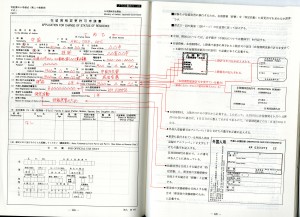

Midnight meeting to decide on the continuation of the class boycott. Photo courtesy Annemarelle van Schayik

Ethnographers at times may want to participate in the environment that they are observing and so did I, but I felt that my hair and eye color would impede rather than support the movement. People who know me know I see Hong Kong as my home, I understand Cantonese and have a deep understanding of the city and Mainland China. Yet, an outsider would just see a foreigner who is ignorant about the deeper issues at stake. The Chinese Communist Party, the Hong Kong’s Chief Executive, Mainland media, as well as certain groups in Hong Kong did indeed assert that the movement was pushed by external forces, and I did not want to fuel those suspicions.

Initially I felt conflicted about not joining, but as I was talking to students I realized I could also become a participant of the unseen and unwritten stage. These included the large-scale consultation sessions on whether or not to continue the class boycott indefinitely, but also the smaller gatherings in which the safety of protesting students and the duties of those who stayed on campus were discussed.

Observing the students behind the scenes was relatively easy as I had been a student at CUHK and as I was a Resident Tutor (American RA), I was already somewhat part of the community. Students knew me as someone they could go to when they had issues so when friendship groups were falling apart due to conflicting views on the police I became the first person students would come to. In their eyes I would not judge their political affiliations and personal feelings of the movement.

The movement seemed the hardest on students who had parents or relatives working for the government because how do you defend them, but also support the movement? One strategy was to help from the sidelines by helping with the collection of food, drinks and masks that would be distributed by other students. Other students spent hours on the street much to the anger of their parents. Their strategy was to simply claim they would be sleeping at the dormitories that night and though parents may have suspected the real motives they had to let go of their, at least in a legal sense, adult children. Some students supported the cause, but not the protesting and they had to deal with attacks from their friends. And a final group simply did not care. All students dealt with psychological issues as everything a person said or did become political and led to personal attacks. University students, critical in classrooms, were suddenly overcome by emotion: you are either with us or against us.

Being at the university listening to these students, offering them comfort and, if asked, advice became, to me, much more meaningful than being on the streets. Media reported on the ruptures, disagreements and diversity of protesters on the street. My participation in the shadows showed me the psychological discomfort of all students, regardless of actual participation. This discomfort was not only due to a polarizing discourse, but perhaps also because of an unfamiliarity with politics. Hongkongers have often been labeled as apolitical and materialistic, yet in recent years the attack on what students consider Hong Kong core values and the perceived increase of Beijing intervention, has led to a rise in political consciousness. The movement and its occupation of Hong Kong roads may not have led to a change, but those who believe in the rightness of the movement and its ideals have not yet given up.

Annemarelle van Schayik is a teaching assistant at the Centre for China Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her M.Phil dissertation focused on the lived experiences of Mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong’s tertiary institutions.