Ryo Morimoto

Although much has been said about the triple disaster—earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdowns—in Japan in March 2011 (hereafter, 3.11), the upsurge of digital records and efforts to archive them in and outside of Japan after these events have been less discussed. These archives are populated not only with born-digital artifacts (e.g., photographs, audio files, video footages, websites and blogs) but also digitalized artifacts (e.g., bureaucratic documents, pamphlets circulated in temporary shelters, 3D renditions of tsunami-damaged buildings). As of June 2017, more than six years after 3.11, there are over 60 digital archive projects, hosted by the local and national governments, private and non-profit sectors, and academic institutions, all with the goal to preserve and transmit digital(ized) traces of the past. Disaster digital archives are both a collaborative space where survivors are delegating “the responsibility of remembering” (Nora 1989:13) and a touch-point where the meaning of reconstruction (fukkō) are performed and negotiated.

In Japan, disaster archives are conceived not merely as a tool for information storage, retrieval and transmission. They also have come to play a key role in disaster reconstruction. In June 2011, the Reconstruction Design Council in Response to the Great East Japan Earthquake released a document entitled “Toward Reconstruction: ‘Hope beyond the Disaster’” which lays out 7 principles of disaster reconstruction design. According to the first principle, the foundation of reconstruction rests on survivors’ ability to mourn and commemorate the dead. Therefore, reconstruction efforts should be geared toward preserving records of the disaster so that they may be analyzed scientifically and the lessons learned from them can be transmitted across generations and throughout the world. However, this document does not specify what is worth preserving, how these materials should be preserved, and what constitutes reconstruction/fukkō from the disasters. These stipulations come to be worked out and materialized through the process of assembling an archive. The act of archiving, as Derrida reminds us, “produces as much as it records the event” (1995: 17).

If the content of an archive matters deeply, then so does its medium. Social media platforms like Twitter have transformed the way disasters are experienced locally and globally (see Johnson 2014; Yoshitsugu 2011) with implications for efforts to archive and memorialize disasters online. Emerging digital technologies enable the seamless recording and instantaneous sharing of an event as it unfolds, transforming each user into a curator and achiever of the everyday (Giannach 2016). Although the digital documentation of disasters might seem as straightforward as snapping a photo on your smartphone, digital records are difficult to preserve, in part because so many of them are produced, and in part because rapid technological change leads to shifting standards of usability and technical formats (Flecker 2003). The vastness, transiency, and instability of digital material require deliberate preservation efforts and continuous investment in human and technological resources.

Moreover, while digital disaster archives can ensure more immediate and broader circulation of information than traditional archives, the openness digital technologies affords has posed limitations on what can be preserved in the present. In the case of Japan, most disaster archive projects shy away from sharing images that include people’s faces, since making these images public risks violating Japanese right of likeness and privacy laws. In order to share these images, archivists must either painstakingly pixel out individual faces, or obtain formal consent from each person appearing in the image.

As I have discussed elsewhere (Morimoto 2014), making disaster archives digital often, ironically and despite the best intentions, involves removing traces of subjectivity and therefore risks the potential forgetting of the individuals involved. For example, the project lead of the Michinoku Shinrokuden archive at International Research Institute of Disaster Science at Tohoku University insists that disaster archives should try to preserve “correct” information about the past events. Although a survivor’s narrative of escaping from the tsunami by a car is certainly a harrowing and memorable story, it might not offer an empirically informed lesson to future, potential victims. During 3.11, huge masses of people attempted to evacuate by car, leading to a traffic gridlock that ultimately increased the number of disaster-related deaths. When archivists historicize the past with the particular goal of reconstruction (“building back better”) in mind, the tendency is sometimes to commemorate the disasters themselves, rather than the lives they touched or destroyed.

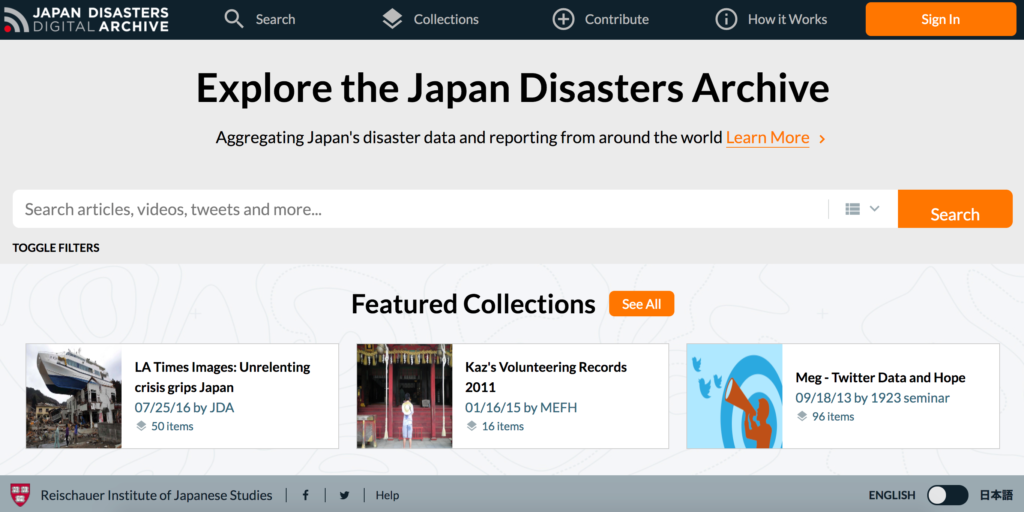

The Japan Disasters Digital Archive (JDA) project at the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University approaches the commemoration of past disasters differently (Figure 1).

Unlike other projects, JDA does not preserve most of its materials. Instead, it hosts links to digital materials shared by over 15 partner projects in Japan and the U.S., thereby acting as a digital networking portal. Moreover, with its personal collection-building feature, JDA is designed to foster a collaborative virtual environment. When users access the archive, they are exposed to an ever-expanding group of fellow archivists: from affiliates of archive projects who share links to their archived materials, to the ordinary user who submits a personal testimonial or blog she discovered online along with her personal photographs of the disasters, to the historian who creates a public collection within the archive in order to understand the interaction between public and private actors in disaster relief efforts. In this way, JDA preserves traces of user participation and interaction, while creating records of the user-oriented reconstruction of past events, and of the collaborative construction of cultural memories in the present.

JDA has been developed with an eye toward pedagogical use. Classroom activities involving JDA at Harvard University, Emory University and Tohoku University illustrate the possibilities of participatory disaster archiving. Students have used JDA in public presentations geared toward teaching the wider public, in Japan and abroad, about the global significance of 3.11 (Figure.2).

Fig 2. Tohoku University students visiting Harvard in September 2015 and giving a presentation about 3.11, intended for the wider Cambridge Japanese Studies and Digital Humanities community. Ryo Morimoto

In this manner, digital archives can lead to off-line, cross-cultural communication and commemoration. U.S.-Japan collaborations around digital disaster archival projects like JDA invites us to consider how novel tools and technologies might challenge the relationship between national identity and collective memory, and the divide between east and west.

Ryo Morimoto is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University, where he also serves as the manager of Japan Disasters Digital Archive. His research examines shifting local perceptions of radiation exposure in post-nuclear accident Fukushima, and the cultural history of representation surrounding radiation, radioactive materials and nuclear energy.