Society for East Asian Anthropology

By Daniel White

September 27, 2023

The global growth of interest in building machines with artificial emotional intelligence sheds surprising light on how engineers in Japan are reimagining diversity through companion robots.

Stories of humans and robots cohabiting harmoniously have long been popular in Japan. In recent years, Japan’s robot manufacturers have increasingly attempted to bring this idea to life by equipping robots with capacities to care for others. For example, Softbank’s four-foot-tall humanoid robot Pepper, introduced in 2014, is marketed as the “the world’s first personal robot that can read emotions.” The animated hologram Azumi Hikari, produced by Gatebox Inc. in 2016, is designed to realize the “ultimate return home” for those who do not otherwise have or prefer a human companion. Fujisoft’s Palro is created as a communication partner for the elderly. And Sony’s pet robot AIBO (1999–2006) and re-released as “aibo” in 2018—a name that combines “AI” with “robot” but that also plays on the Japanese word for “partner” or “pal” (aibō)—is imagined as a constant companion.

Image Credit: Daniel White

Image Description: A small silver canine-like robot is standing on a small stage and facing the camera. To the right of the robot, in the background, is a sign that reads “aibo” in red letters.

Caption: aibo by Sony, featured at a conference on AI in Tokyo in 2019.

In a fieldwork project on the rise of emotional technologies like these, my colleague Hirofumi Katsuno and I ask how practices of modeling emotion in machines are transforming expressions of human emotionality more generally in society. As we have described elsewhere, at the heart of these experiments is heart itself. Across different models of companion and care robots, Japanese engineers attempt to build robots that can express a sense of heart (kokoro) by leveraging artificial emotional intelligence to contribute to a future of human-robot care. Technologies like cameras connected to software that reads facial expressions, for example, or sensors that respond to affectionate forms of touch with haptic feedback can give these robots elementary capacities to display affection.

Intriguingly for many, these machines also raise discussions about whether robots should be granted the right to be considered as legitimate members of Japanese society. While such discussions have stimulated new ideas about how diversity in a future society might be extended beyond human members, they have also raised concerns that a robot-inclusive diversity might come at the expense of other humans.

Robot-inclusive diversity

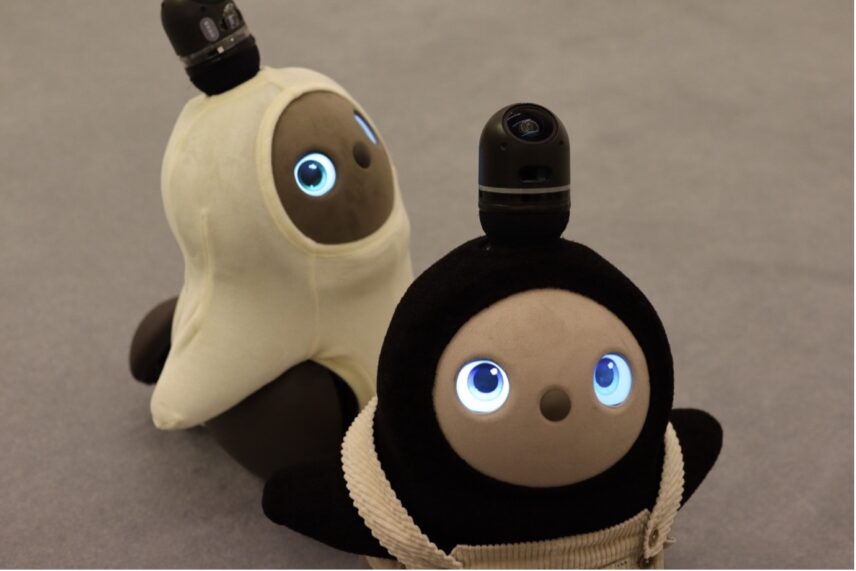

In 2018, the robotics startup GROOVE X introduced a small furry robot on wheels called LOVOT that was designed for just one thing: “to be loved by you.” In the updated release of LOVOT 2.0 in 2022, GROOVE X shifted its marketing campaigns to add to this message on love an emphasis on diversity. A tagline for the new LOVOT on the company’s official website reads, “All to express the diversity and complexity of life. 10+ CPU cores (central processing units), 20+ MCUs (micro controller units), 50+ sensors reproduce behavior like a living thing. A new relationship between robots and people begins here.”

Image Credit: Daniel White

Image Description: Two small brown furry robots on wheels stare at the camera with LED eyes. One is wearing a beige onesie; the other is wearing beige overalls.

Caption: LOVOT by GROOVE X

When GROOVE X introduced its new PR materials on “diversity,” it also institutionalized what the company’s founder and CEO, Hayashi Kaname, had been promoting for years: the idea of a society of genuine human-robot coexistence (kyōzon). Importantly, the use of the word “diversity” (tayōsei) is applied here to refer to all “living things” (seibutsu), a category which GROOVE X proposes could be inclusive of robots like LOVOT. Thus,GROOVE X’s framing of LOVOT as a “living thing” promotes the possibility of welcoming LOVOT into a future society where “diversity” might be extended to nonhuman robot persons.

Prior to GROOVE X’s latest campaign, at an event called Industry Co-Creation held in 2020, Hayashi outlined in detail his vision of an emerging future of robot-inclusive diversity. Building on themes of diversity and social justice—which had gained attention in global advertising cultures—he proposed to an audience of fellow technologists and mass media that his company’s latest companion robot exemplifies a model of diversity.

What kind of era will the world face in the future? I think we are facing an era of the robot native [robotto neitibu no jidai]. Until now diversity has been used to refer to skin color and gender, but in the future, I wonder if the borders between living and nonliving things will be erased. Ultimate diversity leads to peace. I want to create that kind of technology and disseminate it from Japan.

Hayashi is familiar with critiques of the lack of diversity in AI, where AI media images have been criticized for their explicit “whiteness” and AI algorithms for their ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic biases based on machine learning data. By framing the inclusion of robots like LOVOT into society in terms of global social justice, Hayashi presents robots as equally deserving of it as people.

Other robot advocates agree with Hayashi’s perspective that robots deserve a place in societies as a distinct species. The legal scholar Inatani Tatsuhiko has been working for several years on creating legal codes that can promote a society in which humans and robots coexist in harmony. This is imperative, in Inatani’s view, because there exist no uniform codes of law for regulating human-machine relations in the emerging age of artificial intelligence. He suggests that “rather than trying to determine what the essence of machines and human beings is, everyone should think about what kind of society we want first, and then discuss the distribution of legal responsibilities appropriate for that purpose.”

Inatani further recommends that we gradually develop a “synthesized society” between human beings and artificial intelligence by considering “what we want to be with them.” Inatani’s point is that public discussions on the philosophical nature of humans, machines, and AI cannot provide a useful guide for living well with machines. Instead, he proposes to consider human-machine relationships as an open-ended experiment which will yield new models for harmonious cohabitation.

Together, Hayashi and Inatani—among many others—seek to make a place in society for nonhuman robot persons by reconceptualizing the constituency of Japan’s future publics in relation to emotional and interactive capacities. The future of a robot-inclusive society may thus depend less on the makeup of its members than on those members’ abilities to generate what is seen as socially appropriate emotionality toward others, human or otherwise.

More-than-human or all-too-human diversity?

With such an emphasis on the inclusion of robots into society expressed by figures like Hayashi and Inatani, however, there is reason to wonder if the extension of care to robots may contribute to “socially appropriate” emotions that come at the expense of other humans.

While Japanese society has long been admired for its fantastically imaginative fictional characters and robot friends, it has also been criticized for its cultural homogeneity and far less friendly immigration policies. In fact, some ethnographers of Japanese robotics have pointed to an overt lack of diversity among Japan’s mostly male robotics engineers and its implications for the disproportionate number of robots gendered as female. Other ethnographers have raised concerns that certain government endorsements for employing robotic technologies in the elderly care sector attribute more rights to robots than to potential foreign care laborers, particularly from Southeast Asia. Still others have suggested that while robots may not prove to be a replacement for migrant care workers in Japan, they may ultimately deskill the forms of labor in which they are trained. As James Wright has argued in an intimate study of the use of the robot Pepper in a care home in Japan, these robots are still elementary and need the help of human staff to operate. Accordingly, a better word than replacement to describe the impact of care robots is displacement, as “the introduction of care robots displaces skills and practices,” “direct human-human contact,” and “caring for people.”

Such critiques point to practices in Japan of privileging technological diversity by protecting perceptions of human homogeneity. Importantly, these emerging debates over who will be incorporated into future imaginations of diversity in Japan are playing out in a marketplace increasingly focused on feeling. Corporations defend the value of developing robots that care given a Japanese society in which care is in deficit.

Seeking to capitalize off perceptions of increasing alienation and loneliness in contemporary Japan, given an aging society and decreasing birthrates, companion robot companies release prototypes in part to test how people respond to them affectively. Different designs—a furry robot on wheels (LOVOT), a puppy-like pet (aibo), a headless cushion with a wagging feline tail (QOOBO)—evoke different reactions among consumers that are not easy to anticipate or define. Robot makers intentionally focus on positive affect, amorphous feelings of comfort that can be produced by just being with robots. Producers imagine that this palpable but not always explainable form of comfort might expand the abilities for positive emotionality between humans and robots in so much that it is not dependent on the limits and expectations that come with human language, and can thus attend more directly to heart.

Image Credit: Yukai Engineering

Image Description: A woman photographed from the nose down, wearing a white blouse and blue jeans, is sitting on a gray sofa. In her lap she holds a black cat-like cushion robot with a tail and no head. To the right of her on the couch is another gray cat-like cushion robot with its tail sticking out to the left.

Caption: QOOBO

GROOVE X’s robot LOVOT is at the leading edge of building these companions with heart. Despite critiques that investment in robots may discount the value of certain human relationships, GROOVE X argues that the cultivation of affection for fictional and “haptic creatures” like LOVOT 2.0 is not a problem but is rather part of the promise of robot diversity. Hayashi and staff often claim that LOVOT is a “technology that cultivates humans’ power to love”; as Hayashi has qualified in conversation, such love need not be limited to humans or even to nonhuman animals. “When I look at LOVOT, I feel like we are entering an era in which we need not discriminate between humans and robots or even between robots and other living things.”

If the future of diversity in Japan is robot-inclusive, it is also one incorporating a history of people grappling over certain human exclusions. As the current biases of emerging AI and machine learning technologies are increasingly brought to light, both in Japanese and global technocultures, we might also question how optimistic visions of diverse machine-inclusive publics of the future in part trade on discounted visions of human diversity. For robot makers like Hayashi, however, the enlarged capacities of “heart” in LOVOT 2.0 have far-reaching implications for how we pursue human values such as diversity in the future, even redefining emotionality itself in and beyond Japan.

Daniel White is a research affiliate in anthropology at the University of Cambridge and author of Administering Affect. He researches emotion modeling in AI, social robots, and other affective and emotional technologies. His publications and ongoing projects can be found at modelemotion.org.

White, Daniel. 2023. “Feeling Futures of Diversity in Japan.” Anthropology News website, September 27, 2023.

Copyright [2023] American Anthropological Association