Society for East Asian Anthropology

By Jung Eun Kwon

December 27, 2024

It was a beautiful day in October 2022, and the leaves were turning vibrant shades of red and yellow. I was interviewing Yuna (all names in this article are pseudonyms), one of my interlocutors for my research on suicidality—including suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts—among young South Korean women in their twenties and thirties. Yuna, a 34-year-old woman, had been experiencing suicidal thoughts since she was around 13 and had attempted suicide multiple times since the age of 21. Throughout our conversation, I noticed that she kept glancing around the coffee shop and asked to use the restroom several times within the hour and a half we were talking. I felt a sense of concern for her, and my initial instinct was to think that I could or should help her in some way. However, what Yuna said next completely shifted my perspective.

“Usually [for me], an intense suicidal thought lasts about 15 minutes or so, no more than an hour, or it ends within 3 hours at the longest. But in the meantime, with the right intervention, you can get through it. So, I have an automatically-run protocol [created and implemented by myself]—for example, I call a suicide prevention center, and after receiving the consultation, I wait a few minutes. If the suicidal thought is still severe, I just call an ambulance [to stop myself from attempting suicide].”

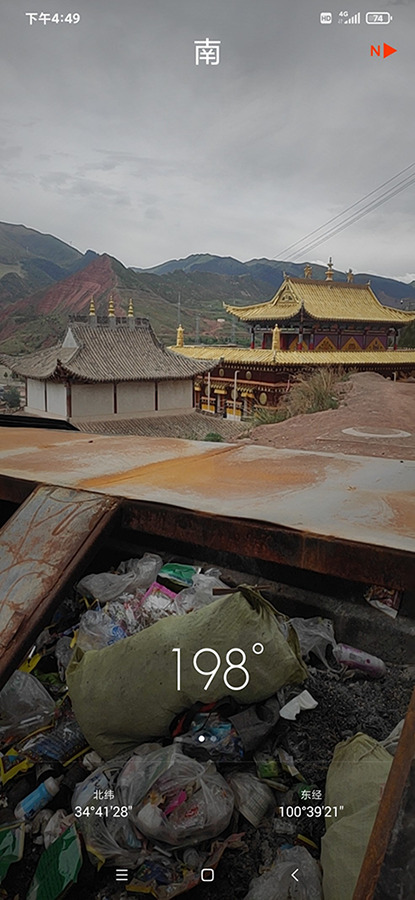

An SOS suicide prevention hotline phone on a bridge in South Korea, providing help for those in crisis. This phone was not used by Yuna during her experience of crisis. Credit: Jung Eun Kwon

Her self-analysis and the creation of her own “protocol” by strategically using institutional care services left me in awe. It led me to reflect on my own assumption that I needed to help her, an assumption partly influenced by South Korea’s broader social discourse on mental illness and suicide. In South Korea (hereafter Korea), mental illness has increasingly been viewed as a psychiatric disorder that requires medical treatment, and suicidality is largely seen as an unusual condition caused primarily by depression. This framework, which stems from disciplines such as psychiatry and psychology, positions people experiencing suicidality as patients or objects of intervention, reducing them to passive recipients of care.

Since the late 1990s, Korea’s suicide rate has risen significantly, ranking among the highest globally since the early 2000s. Although young women do not have the highest suicide rate, their suicidality has sharply increased since the 2010s, in contrast to other demographic trends. In response, the Korean government launched a national suicide prevention project to expand access to psychological and psychiatric support, framing suicide, particularly for women, as a result of ‘mental difficulty” (jeongsinjeok eoryeoum). This view individualizes the issue, also overlooking the creative and diverse care practices these individuals use to manage their suicidality.

The Infographic of 2022 Suicide Motives by Gender and Age Group in South Korea. Data Source: 2024 White Paper on Suicide Prevention (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2024). Credit: South Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare

However, Yuna’s skillful management of her own mental health made me wonder: Is Yuna uniquely skilled at taking care of herself? Or might others who experience suicidality also be this adept at self-care? If so, what do their care practices look like? As I tried to answer these questions, my interlocutors’ various care practices came to my mind.Although most of my interlocutors had received institutional care, such as medication and psychotherapy, they were dissatisfied with these disciplines’ focus on individualizing their experiences. Thus, my interlocutors’ self-care practices tended to stretch toward communal practices, extending attention to society and their roles within it.

Creative Care Practices

I regularly asked the question, “How do you take care of yourself in your everyday life?” during the interviews to explore my young women interlocutors’ care practices, and I was often met with creative and unexpected responses. What impressed me was how these women expanded the boundaries of (self-)care, diverging from institutional care, which emphasizes paying attention to one’s inner self and emotions, as seen in psychology, or to biological factors, as seen in psychiatry. Institutional care often guides individuals to immerse their attention inward, rather than allowing them to explore sociocultural factors beyond their family. Rather, their practices pushed these narrow boundaries, allowing them to reflect on themselves concerning broader social issues prevalent in Korea, such as socioeconomic inequality, discrimination, and marginalized others.

Da-In, a 28-year-old woman working at a small company and living with her mother, offered one such example.She had been writing fantasy novels since high school, a practice she began after experiencing her first suicidal thoughts at 11 and attempting suicide at 14. Initially, she started with short stories, but over time, her narratives expanded into longer works. By the time of our interview, she had completed multi-book-length fantasy novels. She hinted at the pride she felt in her lengthy writing and spoke of her love for writing novels. When I asked her what aspects of writing fantasy novels drew her in, she said it was the ability to create a better world that she hopes to see.

“First of all, [in the fictional world,] the gap between rich and poor is extremely small, there is no discrimination at all, no unreasonable things happen. [People from] this world goes around to civilize other worlds [where the gap is wider, and discrimination and unreasonable things pervade].”

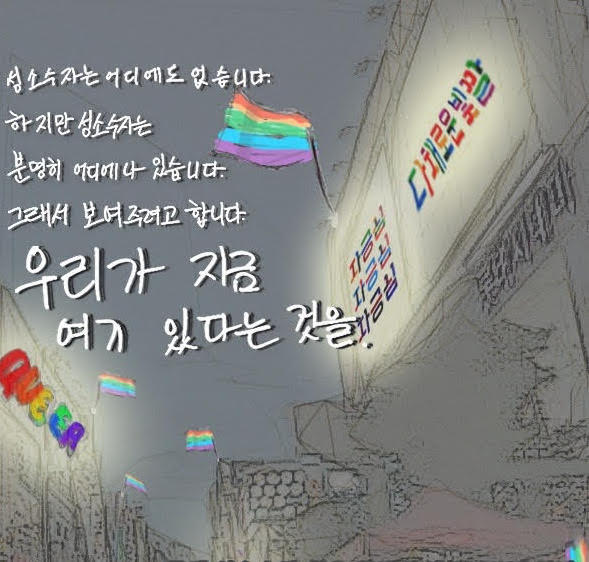

I realized that the setting of her novel both reflected and subverted the difficulties she faced as a teenager. Earlier in the interview, she had spoken at length about her family’s lower economic status, which caused her significant distress during her adolescence. She also mentioned that her classmates disliked her because she was considered “weird or peculiar” for enjoying philosophical books and showing herself off with those books, leaving her isolated most of the time. My interlocutors were deemed unusual in that they desired different paths from what is considered “normal” tracks of life in Korean society. As students, for example, the focus should be on getting into an elite college, then securing a high-paying job with tenure. As daughters, they are expected to obey their patriarchal parents and aim for heteronormative relationships and families to reproduce middle- or upper-class status. The continuous norms and roles imposed throughout their lives contributed to many of my interlocutors’ suicidality, as did the exclusion they experienced when veering from these prescribed paths.

Graffiti reading “Talchul (escape, in Korean)” and “Suicide” on a construction wall in front of high-rise apartments. Credit: Jung Eun Kwon

Against this backdrop, Da-In was flipping the script through her novel on the circumstances that had caused her pain and the prevailing norms, aiming for a society characterized by equality and the absence of discrimination.Imagining and bringing to life a society she hoped to inhabit within the pages of her story brought her a sense of joy and healing. This creative self-care practice reminded me of what Da-In and my other interlocutors commonly shared with me regarding institutional care: they believed it disregarded social issues and did not question social norms, which, in fact, caused their suicidality. Although institutional care was partially helpful to continue their everyday lives through medication and temporary emotional uplift, it could not address their fundamental factors of suffering. In this vein, Da-In was turning toward seeking alternatives that gave her hope, and she was trying to raise her voice through her novel.

Yoobin and Misun, whom I met through a support group meeting, had also been practicing an unexpected kind of self-care. Yoobin, a 32-year-old woman, was a freelancer relying on unemployment benefits at the time, having previously worked as a designer for a startup NGO. Misun, a 36-year-old woman, worked full-time as a support worker for the visually disabled. At the beginning of the group interview with both Yoobin and Misun, they commonly talked about how broader social issues—specifically mentioning the Russia-Ukraine War and climate crisis—were vividly embodied in their suffering, making them feel powerless and their lives useless. They expressed having developed a “deeply rooted distrust against this world” by observing a series of disasters, both far and near.

When I asked them what they do for self-care, their answer first took me by surprise: volunteering. Their response sounded paradoxical to me because I had specifically asked about self-care, not care for others. However, I came to understand their motivations for volunteering as driven by both their own well-being and care for others, especially in light of their discussions about social issues and feelings of powerlessness. Against these feelings, Misun wanted to “feel a sense of accomplishment in this really harsh and unfortunate world,” to feel that she was at least helping others. Yoobin also stated that she is “quite selfish about” volunteering in a similar vein. Rather than being self-absorbed in their emotions and situations, as institutional care often recommends, they directed their attention outward, searching for their space to connect with others, thereby expanding self-care to include care for others and society. In doing so, they situated themselves within a broader world, seeking to contribute to a more livable society.Shedding light on these creative care practices from “suicidal” women shifts our focus from viewing these individuals purely through the lens of their suffering towards recognizing their unique capabilities and resourcefulness. In other words, we realize their active roles in shaping their own well-being rather than viewing them as passive recipients of institutional treatment. This recognition also challenges the narrow boundaries of institutional care, which urges attention inward. In contrast, my interlocutors’ practices of care are oriented not only inward but outward, expanding the meaning of self-care by situating themselves within broader worlds and seeking their roles within it. Similar to Black feminists’ radical perspectives on self-care as a tool for social justice, their care practices encourage us to rethink both self-care and institutional care, emphasizing the need to go beyond self-absorption and foster social connections and collective efforts.

Aaron Su and Jieun Cho are the section contributing editors for the Society for East Asian Anthropology.