Society for East Asian Anthropology

By Xinyu Promio Wang

February 22, 2024

Does using WeChat qualify someone to be “Chinese”?

“So, you are not like a real Chinese . . . I mean, you are just someone who has Chinese heritage, right?” This was what one of my interlocutors, Fangyi, said to me in the middle of our in-person interview after I told her that I do not use WeChat, except for research purposes, as none of my friends or families were on the app. Currently holding a permanent residence visa (永住者) in Japan, Fangyi came to the country six years ago from her hometown, Shanghai, initially as a student. Upon finishing her higher education, she began to work as a medical interpreter, and then later married her Chinese husband, a pharmacist who had acquired Japanese citizenship. After I inquired about the relationship between “not using WeChat” and “not like a real Chinese,” Fangyi explained to me that using the app “is like the Chinese thing. I feel close to home when I’m immersed in this Chinese-language platform while abroad.” For her, it seems like being a “real Chinese” is not simply about having Chinese “heritage,” sharing a Chinese blood tie and celebrating Chinese culture. For her, it is also about “having a constant presence in this Chinese-language environment and sharing your everyday life episodes with families and friends back home so that they can see you, remember you, and recognizing you as one of them, instead of as a bystander.”

Comments like this show how social interactions taking place in digital spaces can be an important means through which Chinese migrants negotiate and represent their senses of identity. As Fangyi indicated, digital media such as WeChat allow many Chinese living overseas to establish a unique public presence in a particularly “Chinese” space. Being seen and visible to her fellow Chinese consequently helps Fanyi not only to maintain her “Chinese roots” but also to acquire senses of being a “real,” somewhat more “authentic” Chinese. However, as I will show, Fangyi’s expression of her “authentic” Chineseness on WeChat as a migrant in Japan is markedly different from, say, that of her friends who use WeChat while living in China. This article aims to nuance the understanding of digital media’s impact on how Chinese migrants see and represent themselves. A closer look at the way people like Fangyi maintain their public presence on WeChat tells us how the use of digital media itself is shaped by desires for mobility as a privilege.

Following the launch of the app Weixin, targeted for mainland China, in January 2011, WeChat went to market in August 2012, created by Chinese tech company Tencent. WeChat and Weixin provide essentially identical functions, such as personal and group messaging, “Moments” (similar to Facebook’s “Wall” function), and news subscriptions. The difference is that Weixin is designated for users whose address is physically registered to China. Free of such territorial restriction, WeChat soon became one of the most popular apps within Chinese-language-speaking publics. Sometimes it is even considered the most important—if not the only—channel through which Chinese migrants and diaspora can maintain their emotional and familial ties with the mainland while living abroad.

While WeChat has some similarities with sites like Facebook and Twitter, it also has some differences. For example, content that users share on WeChat, such as their profiles and posts, are inaccessible to others who are not on the user’s contact list. In this sense, WeChat has a unique social logic that prefers and promotes one’s existing social relationships, rather than encouraging users to discover new connections. This closedness by design explains how Fangyi equates using WeChat with constructing a “constant presence” among her Chinese circles. Keeping up on WeChat gives her a sense that she is being recognized by her close ones as “one of them.” Being constantly present in this setting by, for example, sending out messages and updating information does not simply indicate wanting to be seen by and communicate with anonymous others, as is often taken to be a feature of exchanges on digital platforms. Rather, following the embedded logic of closed publicity, it is driven by the desire to virtually stay close to “us” among families and friends back “home.”

To this point of “staying close to us,” Fangyi stressed the importance of individual messages in managing her diasporic life. She said, “No matter how many years I’ve stayed in this country [Japan], chatting with family is an irreplaceable part of my life. It gives me a sense of intimacy and makes me feel warm.” This perspective is shared by my other interlocutors, who often emphasized that interactions in the closed social spheres on WeChat made them feel connected to “home”—in both senses, as families and as homeland. Another interlocutor, Youan, echoed this point in an interview. Despite having lived in Japan for more than three decades, he said, “Chatting with friends and relatives on WeChat is the most intuitive way to feel my Chinese [roots], like how our culture is always family-oriented, and how we try to keep our friends close [to us].”

However, interestingly, “staying close to us” does not necessarily mean that Chinese migrants like Fangyi wish to identify themselves with this “us.” For example, her “Moments” show how she tries to manage senses of both intimacy and distance as she constructs her migrant self in specific ways. On the one hand, she frequently shares episodes from her everyday life in Japan, posting several photos coupled with short writings two to three times a day. On the other hand, the majority of these posts are written either entirely in Japanese or in a combination of simplified Chinese and Japanese, being partially or completely inaccessible to those who do not understand Japanese. In fact, when I counted, out of 154 “moments” posts she created over three months, only 19 of them were fully written in simplified Chinese.

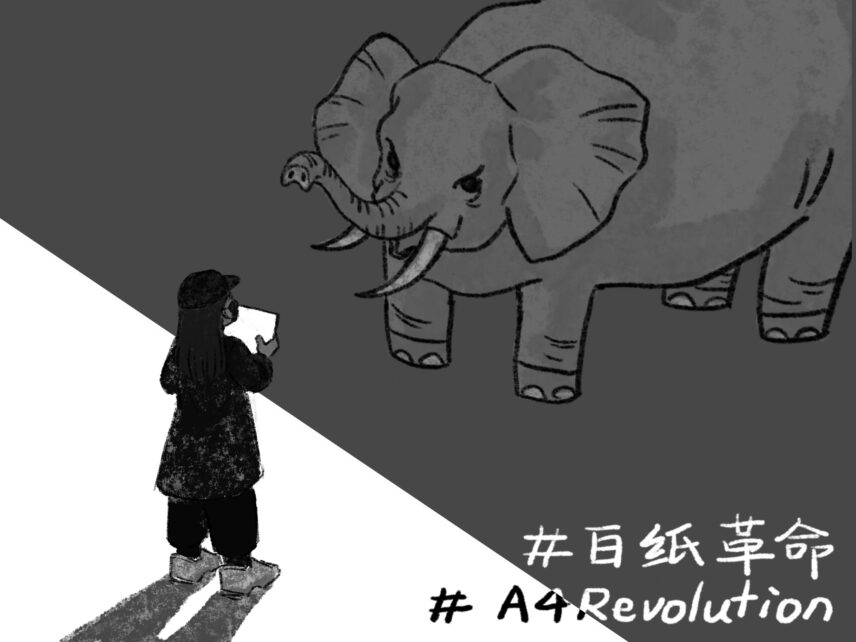

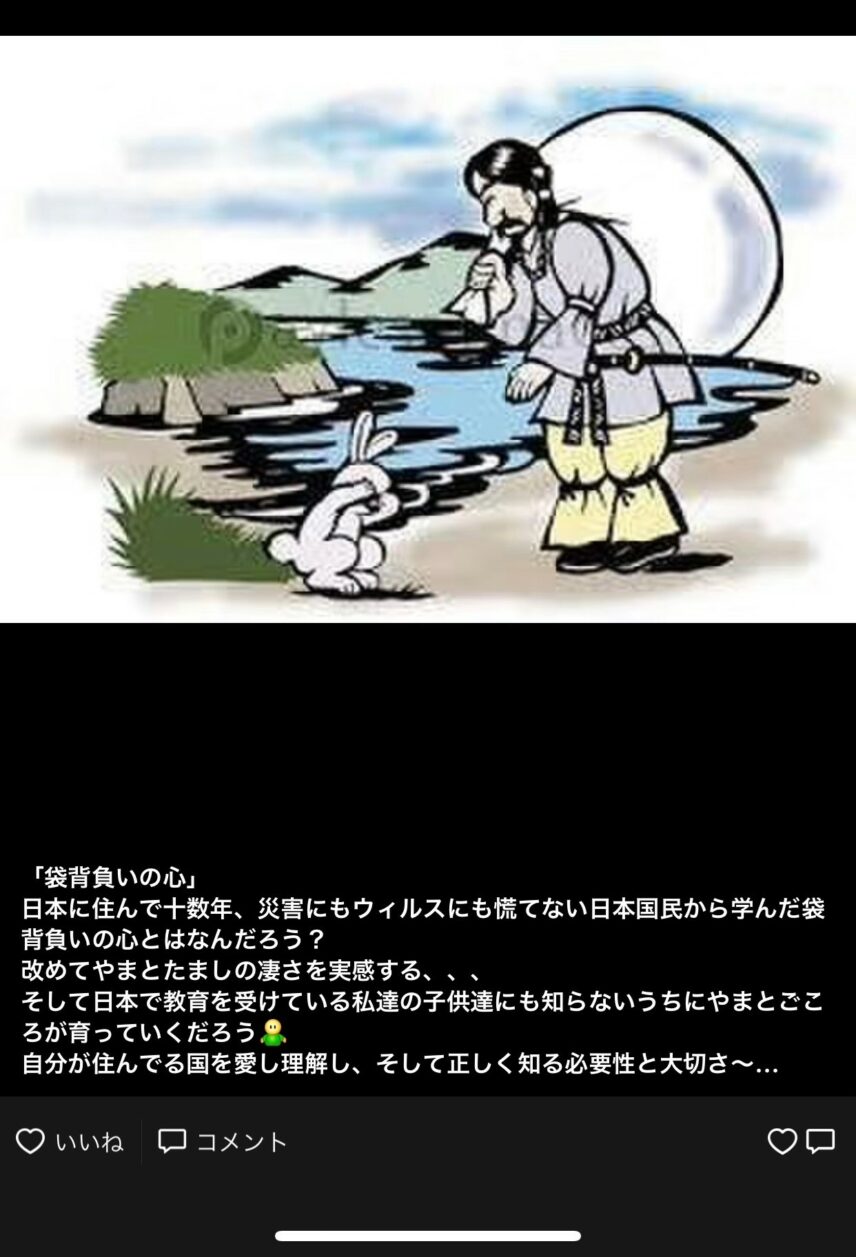

A screenshot of a man in traditional Japanese clothing talking to a rabbit; the text message below describes Fangyi’s thoughts of “loving the country you reside in.”

Screenshot of one of Fangyi’s “Moments” posts. (A screenshot of a man in traditional Japanese clothing talking to a rabbit; the text message below describes Fangyi’s thoughts of “loving the country you reside in.”) CREDIT: AUTHOR

About her Japanese posts on WeChat, Fangyi confirmed to me that most of her WeChat contacts cannot read Japanese and therefore wouldn’t be able to understand her posts. Moreover, when Fangyi wants to communicate in Japanese, she uses a separate app called LINE, arguably the most popular messaging app in Japan. When I asked her why Japanese is her main language in cultivating her online presence on WeChat, she said,

“As someone who lives in Japan, I feel naturally I should write things in Japanese because I’m part of its culture . . . and so my friends know that I’m abroad. I may not necessarily enjoy a better material life here in Tokyo compared to my friends in Shanghai. But we are different. (I want to show that) I’m not your typical, average Chinese who has never seen a different world [outside China].”

As with Fangyi, digital media platforms can inspire a complex range of self-positionings and identifications among its users. In contrast to her private messages, Fangyi’s language choice in the public realm of “moments” seems more like a strategy to distinguish herself from, instead of aligning herself with, those “typical” Chinese who are “at home.” In this sense, her transnational mobility and foreign-language skills acquired through that position serve as capital that she can leverage to perform and claim her identity to be, say, an “above-average” Chinese.

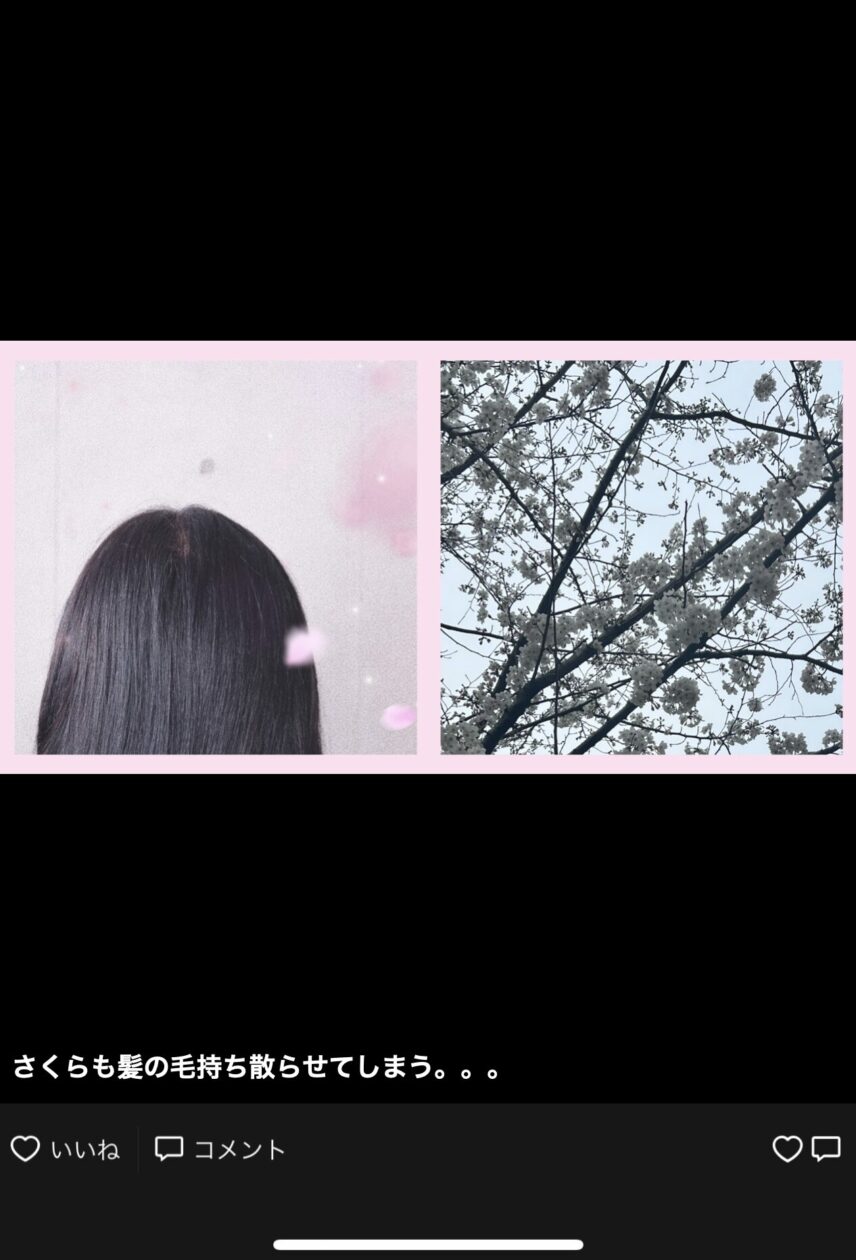

A screenshot of a picture that consists of two photos. The one on the left shows the back side of Fangyi’s head, and the one on the right is a photo of cherry blossom; the Japanese text message below translates as “both the cherry blossom and my hair wither away.”

Screenshot of one of Fangyi’s “Moments” posts. (A screenshot of a picture that consists of two photos. The one on the left shows the back side of Fangyi’s head, and the one on the right is a photo of cherry blossom; the Japanese text message below translates as “both the cherry blossom and my hair wither away.”) CREDIT: AUTHOR

In my digital ethnographic observation, I found that many Chinese migrants tend to manage their online presence in ways that are similar to Fangyi’s. Despite the fact that WeChat is a platform designated for Chinese-speaking audiences, I frequently see Chinese migrants using languages such as Korean, French, German, and Italian in relation to their respective migratory experiences. In this way, whether consciously or unconsciously, their privilege of international mobility becomes leverage that allows them to de-homogenize a uniform Chinese identity and to allude to the difference between themselves and their nonmigrant counterparts in the publicly visible digital sphere. While understanding migrants’ identities as a fluid and multilayered concept is not new, this illuminates that such multilayeredness is partially inspired by their engagement with multipublic digital spaces. In this sense, their experiences invite us to think about the way that our own identities and relationships with our home(lands) are now constructed in relation to digital connectivity and technological affordance.

This piece is part of the SEAA series “The Future of the ‘Public’ in East Asia.” Aaron Su and Jieun Cho are the section contributing editors for the Society for East Asian Anthropology. Contact them at jieun.cho@duke.edu and aaronsu@princeton.edu.