Society for East Asian Anthropology

John Ostermiller

March 28, 2025

Read the article on Anthropology News

Migration is not just about “getting there” but also “making it.” What does it feel like when you can’t fit in your host society as the “right” kind of migrant?

For countless Muslim migrants, Japan represents opportunity and a chance for upward mobility. Yet in a country often imagined as homogeneous and “secular,” what do opportunity and mobility look like? After all, migration is not just about “getting there,” but “making it.” How do race, power, and social class influence migrants’ experiences in Japan?

Since the 1970s, Japanese society has increasingly relied on migrants to fill a variety of jobs, although the government has been slow to acknowledge or support them. Today, three million foreign residents make up about 3% of Japan’s total population. Between 2018 and 2023, foreign labor grew by over 40% with a growing number of workers coming from South and Southeast Asia. Although the Japanese government does not record the religion of migrants living in Japan, scholars estimate that 230,000 Muslims are living there as of 2020. While an increasing number of migrants coming to Japan are from the Muslim-majority countries of Malaysia and Indonesia—the largest Muslim country by population—the Muslim community in Japan is made up of migrants from all over the world.

Credit: John Ostermiller

View of the Shizuoka Masjid (Mosque), located on the western edges of Shizuoka City, the author’s primary fieldsite. Prior to the opening of the mosque in 2019, the local Muslim organization operated a prayer room out of its offices in downtown. Of the dozens of properties, they offered to buy, the only one who would sell to a Muslim organization was on the edge of the city.

“Passing” in Japanese Society

Narratives linking “blood” to “culture” shape the experiences of migrants in Japan. These narratives posit that Japanese “blood” is unique—and without it, one cannot “truly” understand Japanese culture—a perspective that extends to social perceptions of migrants.

In Japan, migrants aren’t called imin (immigrants), but rather gaikokujin (foreigners) or the abbreviated gaijin (outsiders). Historically, Japanese immigration policies have favored nikkeijin—foreigners of Japanese descent—with the assumption that their “partial” Japanese “blood” would give them an innate understanding of Japanese customs. Unfortunately, nikkeijin have often faced harsh criticism for “looking Japanese” but not “acting Japanese.”

Foreign residents and Japanese of mixed ancestry try to “pass” as Japanese to avoid the stigma of being a foreigner. However, not all foreigners are treated equally in Japan. The Muslim migrants I interviewed mentioned that most Japanese people they encountered had little experience with Muslims or knowledge of Islam. They also discussed the unspoken interactional rules between Japanese and non-Japanese people: white westerners are often treated better than non-western, darker-skinned foreigners. In other words, migrant mobility in Japan is shaped by two factors: whether or not you can “pass” as Japanese, and what kind of foreigner you can “pass” as.

In Japan, “whiteness” is highly desirable, and blonde-haired, blue-eyed white Western men are often seen as the “ideal” foreigners. Meanwhile, Blackness and darker skin are stigmatized. Being Muslim complicates this hierarchy. Because Japanese media often portrays “Muslims” as a homogenous group of Middle Eastern people prone to religious violence, Japanese people may conflate migrants’ religion with their “race,” or fear that Muslims’ customs pose a threat to Japanese communities. My friends Hamza and Madiha share their stories as Muslim migrants living in Japan who struggled with “passing” in various situations.

Credit: John Ostermiller

Preparing for Eid in June 2024 at the Shizuoka Mosque, a converted warehouse located along Mochimune harbor’s waterfront. Because of the small number of mosques in Japan, some Muslim migrants may only visit a mosque once or twice a year for Ramadan and The Feast of the Sacrifice (Eid).

Hamza: What is White Passing?

For many Muslim migrants, living in Japan is an exercise in adaptation. Life is not organized around the five daily prayers, mosques are rare, and finding halal food can be challenging. Hamza, a Palestinian English teacher living in Shizuoka for over 30 years, said it best: “To be frank, this is a country that doesn’t do things according to Islamic law. If you want to do things according to Islamic law, why the hell are you here?” Hamza moved to Japan after meeting his future wife on a flight to India where he was attending college.

When Hamza first arrived in Shizuoka in the 1990s, clusters of schoolchildren would excitedly shout “hullo!” and “gaijin!” (“outsider”) whenever they saw him in the neighborhood. Hamza felt that his appearance was a significant barrier to finding work in Japan because he “didn’t look white.” One of the most common jobs for foreigners in Japan—especially for white Westerners—is teaching English. Hamza is fluent in English. Growing up in 1960s Palestine, he used to translate TIME Magazine articles into Arabic with his friends. Despite his fluency, Hamza’s first job was assisting his father-in-law with his struggling roofing business.

Hamza attributed his difficulty in securing a teaching job to Japanese assumptions about race and ethnicity: “In Japan, there is a kind of complex that only whites and Westerners can be native English speakers.” Hamza and I crossed paths several times at the Shizuoka Mosque before he introduced himself, and I always assumed he was a Western expatriate living in Japan. While I perceived Hamza as “white passing,” many Japanese people did not share this view.

For Japanese residents—especially those with limited personal experience with foreigners—Hamza is not perceived as white. Who counts as “white” is shaped not only by broad ideas of whiteness, but also by local assumptions about what white people “should” look like. In Hamza’s case, the expectation was that white foreigners should be blonde-haired and blue-eyed. His situation was further complicated by the portrayal of Palestinians in global media: “I couldn’t say I was Palestinian, right? Back in those days, people had the impression that Palestinians were guerillas. I couldn’t even say I was from the Middle East.” Racially ambiguous and unable to “pass,” Hamza struggled to find “real” work that paid a steady wage. With the help of his wife and in-laws, Hamza was able to secure a loan from a Japanese bank and open his own school. By marrying a Japanese citizen, Hamza gained the flexibility and mobility needed to work, live, and succeed in Japanese society.

Credit: John Ostermiller

View of Mt. Fuji from Mochimune train station. Getting to Mochimune may only be a 10-to-20 minute train ride, but the mosque itself is another 15-to-20 minute walk from the station. Commuting to the mosque is one of the major issues for Muslims in Shizuoka.

Madiha: “I don’t even feel human sometimes”

Madiha’s experiences sharply contrast Hamza’s. Madiha, an African European woman in her twenties, is pursuing her PhD in a major Japanese city. Born to African immigrants, she grew up in a small European town. Madiha’s ethnicity, religion, nationality, and gender have complicated her life in Japan.

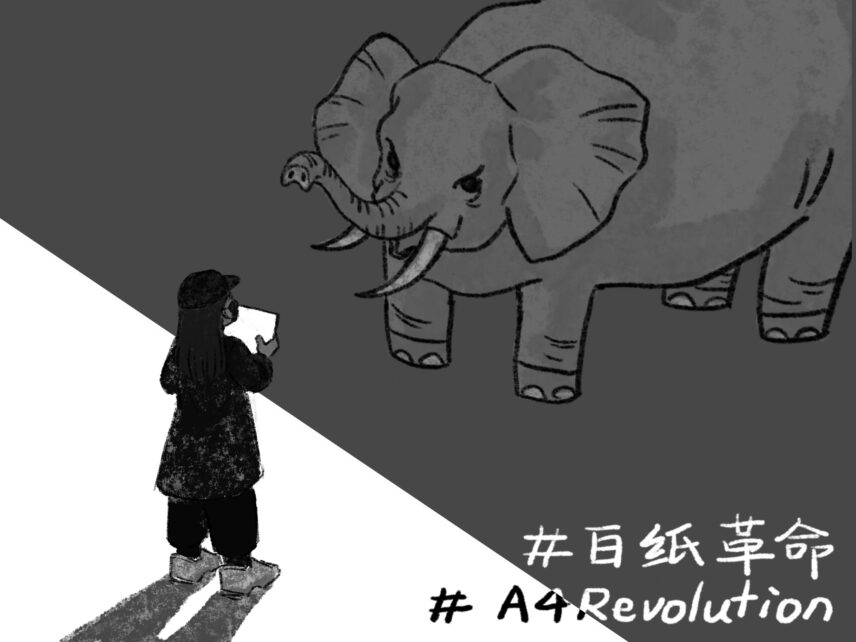

Madiha often feels conflicted about wearing her hijab. Numerous European countries have debated whether to allow Muslim women to wear “pious” religious garments like the hijab. At first, Madiha felt that Japan was a “safe” place to wear the veil, especially in the wake of Israel’s 2023 invasion of Palestine. However, her current relationship with Japan isn’t a “love-hate,” but rather “hate-hate.”

As a dark-skinned Muslim woman in Japan, Madiha is explicitly marked as a racial, religious, and gendered subject. In the United States, some Latine persons attempt to “pass” as white by changing their names and behavior. Likewise, African men in Japan have increased their social mobility by adopting African American names, fashion, and speaking styles. But for Madiha, this option isn’t viable. She doesn’t want to be seen as African American; she wants to be acknowledged as African European. Madiha described the surprise on her Japanese friends’ and acquaintances’ faces when she told them she was from Europe: “I could see the confusion on their faces. Like they were thinking, ‘She’s (European), but she’s Black. So, she’s not telling us where she really comes from.’”

As a Black Muslim woman, Madiha deviates from the “ideal” foreigner archetype in Japanese society—typically envisioned as a white, presumably Christian or non-religious man. Madiha’s skin color and hijab are not “coded” as European in the minds of many Japanese people she encounters. While some African migrants successfully pass as Americans, this doesn’t work for Madiha. Madiha continues:

“Ever since I’ve been in Japan, I’m reminded of how Black I am. Or how foreign I am. And there are different layers. If you’re Asian or white, it will be different… But you’re going to be praised, too. Not me. I’m an overweight, introverted Black woman. I’m not super cool. People always thought I was American. This American girl that is cool and sassy. And that is not what I am at all. I do not fit the stereotype. It was a struggle. It still is a struggle. I’m still perceived as someone that is dangerous [because I am Black and Muslim]. I don’t really feel like a woman here. I don’t even feel human even sometimes.”

This struggle to be accepted and acknowledged has impacted Madiha in other ways. After enduring constant staring—especially on trains where people would avoid sitting next to her—Madiha changed the way she wore her hijab. She experimented with different scarves and head wraps, hoping to look like just “another African migrant” rather than a dark-skinned religious foreigner. This also affected Madiha’s physical mobility: she rarely goes out and works from home whenever possible. Madiha attended mosque services a few times but stopped after receiving judgmental stares from Muslims who saw her without her hijab outside the mosque. Unable to ignore her religious convictions or make herself legible to her Japanese friends and colleagues, Madiha is stuck. She feels rejected by both her religious peers and Japanese society at large.

Migrant (Il)legibility and (Im)mobility

Hamza’s and Madiha’s experiences highlight how being Muslim in Japan complicates migrants’ abilities to pursue the opportunities that initially drew them to the country. Their stories bring to light the unspoken hierarchy of foreigners in Japanese society, revealing a clear preference for white, Western men. As a result, “making it” in Japan often requires migrants to alter their appearance, speech, and behavior. However, for pious dark-skinned Muslim women like Madiha, it is as impossible to change one’s skin color as it is unconscionable to take off one’s hijab. Understanding migrants’ experiences requires us to pay attention to how multiple factors—like race, religion, gender, class—shape the opportunities and challenges they encounter. This includes recognizing that Western ideas about whiteness permeate other countries as well. Although migrants may come to Japan for similar reasons, like professional or educational opportunities, their actual experiences in Japan can differ greatly.

Alex Wolff and Yanping Ni are the section contributing editors for the Society for East Asian Anthropology.

The family members and their supporters stand on guard as the police readies to remove the altar from the site any moment. (CREDIT: SHINJUNG NAM)

The family members and their supporters stand on guard as the police readies to remove the altar from the site any moment. (CREDIT: SHINJUNG NAM) These memorabilia belong to Ms. Sunny Kim, a long-time interviewee of the author, who has matched each of them with one of her daily objects, including her handbags and her cellphone case. (CREDIT: MS. SUNNY KIM)

These memorabilia belong to Ms. Sunny Kim, a long-time interviewee of the author, who has matched each of them with one of her daily objects, including her handbags and her cellphone case. (CREDIT: MS. SUNNY KIM) In the photograph taken on the 49th day of mourning, the poster reads, “Please, remember us.” (CREDIT: SHINJUNG NAM)

In the photograph taken on the 49th day of mourning, the poster reads, “Please, remember us.” (CREDIT: SHINJUNG NAM)