Society for East Asian Anthropology

By Sera Yeong Seo Park

July 5, 2022

For the bereaved of Sewol and activists in solidarity, the yellow ribbon is a powerful index of remembrance, political dissent, and community making.

A day before the seventh anniversary of the sinking of the Sewol ferry, I was sitting alongside a handful of activists in a snug children’s library in Yongsan District, with piles of yellow foam boards and silver chains stacked in front of us. The members of the Yongsan 4.16 Collective were determined to fashion as many yellow ribbons as possible to be circulated in the school district the following morning. This late-night ribbon crafting had become a ritual of sorts to memorialize the sinking of the Sewol ferry on April 16, 2014. April, for those who gathered there, was imbued with harrowing memories of the disaster and the weight of the guilt that they carried as helpless witnesses to the tragedy.

The Yongsan 4.16 Collective was just one among many local clusters of Sewol activism that I came to know during my fieldwork in Korea. Independently organized, these grassroots networks performed paramount work in sustaining the movement nationwide, in solidarity with bereaved family members calling for remembrance, truth, and accountability. What animated these spaces was the yellow ribbon—what was initially a token of condolence, and, later, of multiple affects such as grief, anger, and remembrance. Notably, many who took up the work of Sewol activism often deliberately avoided calling themselves “activists” (hwaldongga) because what they were doing, they told me, fell short of the single-minded, unfaltering commitment they associated with activist work. After all, they diverged from Namhee Lee’s account of the ideological, protest-oriented struggles of the anti-authoritarian, pro-democratization movement in the 1970s and 80s led by the Minjung—common people. Yet, as the Sewol movement illustrates, what it means to “act” was also changing with the historical and cultural currents of Korea. The yellow ribbons that I encountered on the field fashioned new, expansive modes of solidarity, opening up spaces for memorialization of the Sewol disaster and permeable connections within and beyond circles of activists.

The Sewol ferry disaster and the yellow ribbon

The Sewol disaster claimed the lives of 304 passengers, 250 of whom were high school students on a fieldtrip to Jeju Island on the southern coast of the peninsula. It quickly became clear that this was an utterly preventable tragedy. The MV Sewol ferry had been illegally modified to carry more cargo and passengers than originally designed; when the ferry took an abruptly sharp turn on the morning of the 16th, the captain and the crew members were among the first to escape, and passengers were told to “stay put.” Those who followed the instructions through the loudspeakers never made it out of the ill-fated ferry, while the dispatched coast guard forces merely circled around during the critical minutes of the rescue operation.

Caption: October 2020, Jeonnam province, Korea. Activists demand the truth of the Sewol Disaster, as part of the Truth Bus (jinsilbeoseu) campaign. Sera Yeong Seo Park.

The sinking of the ferry quickly incited a widespread social movement in South Korea, founded on condolence for the victims, guilt in having condoned power structures that failed citizens, and collective determination that “things must change.” The Sewol movement broadly drew on the repertoires and networks afforded by the simin (citizens’) movements, which emerged after the installation of democratic governance. These relatively recent movements foregrounded what Amy Levine describes as “liberal, identity-based, non-violent approaches” to political change, relying on the language of human rights and legal action. Yet the Sewol movement also maintained distinct effects and affects of its own. The yellow ribbon first emerged as a symbol of hope for safe return of the missing passengers: social media users embellished their profile photos with yellow ribbons and the slogan, “May one small movement bring a great miracle.” As the chance of victims returning grew fainter with each passing day, the yellow ribbon morphed into a symbol for remembering the victims and expressing solidarity with their families’ demand for truth and justice.

Refusing to remain idle in the aftermath of this shattering loss, citizens turned to the yellow ribbon to cope with, and make something out of, their grief. A collective that came to be known as the Gwanghwamun noran ribon gongjakso (Gwanghwamun yellow ribbon studio) took up a small corner across the memorial altar set up for the victims in Gwanghwamun plaza in Seoul’s city center. While some showed up daily, any passer-by could join in as they wished. After the physical studio was disbanded and the altar was taken down, other yellow ribbon studios emerged nationwide, most of which are run by volunteers who create and distribute ribbons to the wider public.

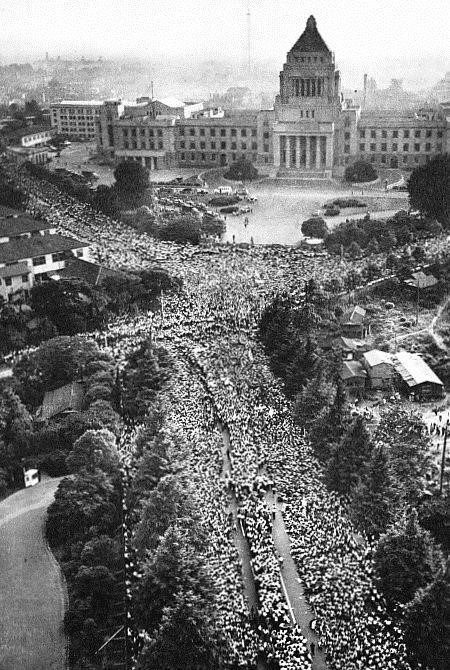

At the height of the mass protest denouncing the corruption of the Park Geun-hye administration and demanding the president’s impeachment, the yellow ribbons came to adopt another layer of meaning. The bereaved of Sewol took to the streets to demand truth and accountability, mobilizing a post-disaster campaign of unprecedented scale in Korea. Grievances against the administration were already simmering to the brim when Park’s flagrant abuse of power came to light at the end of 2016. In the weeks leading up to March 2017, Seoul witnessed 20 consecutive weekends of mass mobilizations demanding that Park step down from office―protests unparalleled in scale and reach, writes Nan Kim, since the democratic uprising in 1987. Yellow ribbons were among the most pervasive motifs in these anti-Park rallies, donned not only by the bereaved but by innumerable other citizens who took to the streets, testifying to the inextricable tie the disaster shared with the wider denunciation of the Park administration.

Caption: The owner of the thin and frayed yellow ribbon on the right had been carrying it with him since 2014, soon after the sinking of the Sewol Ferry. Sera Yeong Seo Park

As the Sewol movement expanded, Liora Sarfati and Bora Chung argue that yellow ribbons served as an “affective symbol” that “tie[d] together the personal grief and shock from the disaster with broader public concerns such as personal safety and corruption,” while also being incorporated “into other social injustice debates and demonstrations.” Nan Kim now dubs the yellow ribbon “the most prevalent and durable material metaphor of progressive dissent” in Korea. According to Kim, it was precisely the diverse significations of the yellow ribbon––not just militancy and dissidence, but also hope and the ribbon’s moral register––that gave the symbol such a wide reach.

Materiality, sociality, and the yellow ribbon

My ethnographic work suggests that yellow ribbons were powerful because they fostered a sociality in which people forged ethical and affective attachments to the Sewol cause. In the case of the Yongsan 4.16 Collective, for instance, the crafting sessions kindled conversations about what the disaster meant for each person in the room. On the eve of the seventh anniversary, Eunhee, a seasoned activist who led the Sewol movement in the district, invited everyone to share what had brought them there. Eunhee’s invitation sparked a string of reflections as we went around the room, from a 20-year-old first-timer who had put together events in memoriam for the victims throughout middle and high school to a woman in her forties with children of her own around the age of the deceased students and for whom the tragedy hit too close to home. As the night drifted along and yellow ribbons piled up before us, a chorus of stories emerged. The simple, manual labor of crafting ribbons had woven us together into a collective bound by a common commitment to remembrance.

Caption: A family collects ribbons during a street campaign held in the Yongsan district, on the 7th anniversary of the Sewol Disaster. Sera Yeong Seo Park.

Distributing the ribbons on busy streets was also an important part of the project of remembrance. Most pedestrians would carry on without giving a second look at the yellow ribbon campaigns, a bitter testament to the waning presence of the Sewol disaster in the public memory. But there were always a few memorable encounters that reminded me and my fellow campaigners of the power of this symbol as it travels. The owner of a small restaurant across the street from where we held our campaign for the 6th anniversary, for instance, approached us to ask whether he could chip in with a donation; an elderly man inquired if he could take five more for his friends. Several people retracted their steps once they heard the word “Sewol” to skim through the bundle of ribbons laid out on the table. Each of these encounters, albeit ephemeral, facilitated a continual circulation of the yellow ribbons, kindling diffuse, far-reaching networks of solidarity through everyday material encounters.

Towards a wide movement

The yellow ribbon became a versatile symbol standing for, yet also exceeding, the critique of systemic failures and corruption that the Sewol Disaster had brought to the surface. For the bereaved of Sewol, a chance encounter with a yellow ribbon dangling on a stranger’s backpack could be a poignant reminder that theirs is not a solitary fight. For activists across the peninsula, the crafting and distributing of the yellow ribbon is a small yet crucial means to keep the memory of the Sewol disaster alive.

The Sewol movement, according to an activist I met in the field, would be viable insofar as it is a “wide” movement, one with blurred boundaries between its locus and the margins, and between sporadic and sustained engagements. In this formulation, the loosely organized ribbon-crafting sessions and the fleeting encounters with the recipients of the yellow ribbon were as crucial as events of more pronounced political energy and impact, such as protests. The yellow ribbons were crucial for achieving this width, their crafting and circulation inviting diverse repertoires of solidarity without circumscribing what solidarity is or ought to look like.

Sera Yeong Seo Park is a PhD student in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. Her doctoral dissertation examines the social movement that emerged in the aftermath of the Sewol ferry disaster in South Korea. Her research interests include activism, emotions, affect, and the anthropology of ethics and morality.

Cite as: Park, Sera Yeong Seo. 2022. “Crafting Solidarity after the Sewol Disaster.” Anthropology News website, July 5, 2022.

Copyright [2022] American Anthropological Association