By Jennifer Bruno (Yale University) and Joshua Hotaka Roth (Mt. Holyoke College)

Jennifer Bruno: What inspired you to undertake your research with Japanese Brazilian migrants in Japan?

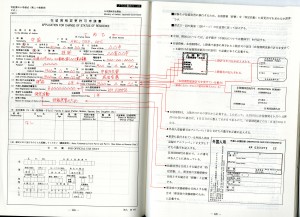

Joshua Hotaka Roth: There was a lot of excitement about globalization and transnationalism when I was in graduate school in the early 1990s. I had befriended several Japanese Brazilians when I was in university in Japan in 1989, just as the large labor migration from Brazil to Japan was beginning, so the project just presented itself to me. By the time I conducted research in 1995, there were about 250,000 Brazilians, mostly of Japanese ancestry, working in Japan. Some of the early globalization literature celebrated flows, the possibility of multiple identifications beyond the taken-for-granted local or national, and the rise of creole cultural forms. But I found that for many Japanese Brazilians, migration to Japan involved a reconfiguration of social relations in an attenuated form. I’m reminded of David Graeber’s reading of enslavement as involving the violent tearing the person, defined as a unique conflux of relations, from that web of relations. Of course migrants have agency while slaves do not, but it would be a mistake to assume freedom of choice when choices are always constrained, and when migrants keenly felt their displacement from established webs of relationships.

Joshua Hotaka Roth: There was a lot of excitement about globalization and transnationalism when I was in graduate school in the early 1990s. I had befriended several Japanese Brazilians when I was in university in Japan in 1989, just as the large labor migration from Brazil to Japan was beginning, so the project just presented itself to me. By the time I conducted research in 1995, there were about 250,000 Brazilians, mostly of Japanese ancestry, working in Japan. Some of the early globalization literature celebrated flows, the possibility of multiple identifications beyond the taken-for-granted local or national, and the rise of creole cultural forms. But I found that for many Japanese Brazilians, migration to Japan involved a reconfiguration of social relations in an attenuated form. I’m reminded of David Graeber’s reading of enslavement as involving the violent tearing the person, defined as a unique conflux of relations, from that web of relations. Of course migrants have agency while slaves do not, but it would be a mistake to assume freedom of choice when choices are always constrained, and when migrants keenly felt their displacement from established webs of relationships.

JB: How has the situation for Japanese Brazilians changed?

JHR: The Japanese Brazilian presence in Japan has shifted a lot in the last 20 years. The numbers of Brazilians in Japan peaked at about 311,000 just before the financial crisis in 2008. Today with the Brazilian economy doing better, only about half remain in Japan. In the 1990s, most were on temporary visas that had to be renewed every one or three years. Most worked in temporary factories positions that they really didn’t enjoy. The majority that remain are committed to a long-term residence in Japan, and some see it, much more than in the past, as their permanent home. Japanese Brazilian residents in Japan still face uncertainty, but compared to the past, more have moved into stable employment, started their own businesses, raised children, and established new webs of relationships.

JB: Could you talk about the transition from your first project to what you’re doing now? What questions have guided your research?

JHR: My current research is on Japanese automobility. I’ve published on the history of driving manners and discourses on emotion and risk. I’ve written about gender and driving, and am looking into a project on minorities and driving. But how did I first get into this? I’m not a car fanatic. I did work on a car assembly line for my first project. But the real link was the conceptual focus on acceptable levels of risk among Japanese and Japanese Brazilians workers that emerged in a chapter on work-related accidents. Subsequently, I wanted to go to Brazil and learn more about the communities from which many of the migrants I met in Japan had come. Among other things, I ended up writing an article on Japanese Brazilian gateball (a form of croquet) in São Paulo. At a time when the fear of crime was widespread among middle and upper middle class Paulistanos, it was curious that middle class Japanese migrants willingly occupied public spaces, rather than retreating behind the numerous fortified apartment blocks and gated communities. Once again, I found myself inadvertently writing about the circumstances that may affect acceptable levels of risk. But the risk literature often makes for pretty dreary reading. I decided on automobility because it involves questions of risk and its governance, but also of desire. Along the way, however, I’ve also become interested in questions involving maps, spatial orientation, and the cultural category of “hōkō onchi” (directionally tone-deaf) and currently am working on an article about getting lost in Tokyo.

Joshua Hotaka Roth is Professor of Anthropology at Mount Holyoke College. His publications include Brokered Homeland: Japanese Brazilian Migrants in Japan (Cornell Univ. Press), “Mean Spirited Sport: Japanese Brazilian Croquet in São Paulo’s Public Spaces” (Anthropological Quarterly), and “Heartfelt Driving: Discourses on Manners, Safety, and Emotion,” (Journal of Asian Studies).

Jennifer Bruno is an M.A. student in East Asian Studies at Yale University

Please send news items, contributions, and comments to SEAA Contributing Editors Heidi K. Lam (heidi.lam@yale.edu) or Yi Zhou (yizhou@ucdavis.edu).